Former Daily Trail blogger and founder, Dennis Williams, sent me a link to an Australian artist (Adam Murphy) who creates mashups of different comics characters and styles, such as Charlie Brown and Calvin & Hobbes; The Phantom and Indiana Jones; and Tin Tin and Indiana Jones. Check out his impressive work on Instagram: @adammurphyart. Mark Trail does not seem to have been one of the inspirations.

The Tin Tin reference is especially significant, as the original Belgium strip proves that adventure comics with good suspense, drama, and even humor do not have to be depicted in what many consider a proper “realistic” style (e.g. Judge Parker, The Phantom, Flash Gordon, and vintage Mark Trail). Having noted this, I do not propose that Rivera’s current interpretation reaches the level of Tin Tin in either style or plotting. Well, I think it did in the beginning (as I have said before); and it could, again, if she wanted.

As for this past week, we have endured days of Bill Ellis on the phone with Mark, convincing him to take on an assignment to help locate a film director who disappeared inside a house, where the house apparently is locked down and filled with lions and actors involved in the director’s current film. Does this sound absurd? Of course it does, in pretty much every which way you can imagine! If you want more details, you’ll have to scan the previous posts; I won’t repeat them here. What I will say is that, unless this house is on scale with the Biltmore mansion in North Carolina, I don’t see how this works. But, we can meditate for now on today’s topic.

Once again, Rivera chooses a topic geographically related to Mark’s current story: California. And once again, Rivera ends the discussion with a non sequitur (“social climber”).

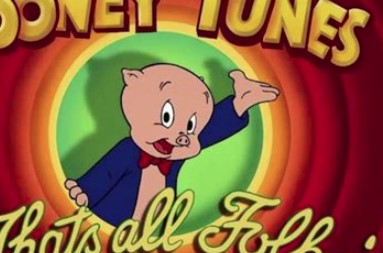

Art Dept. In the “penultimate” panel (that might sound snooty, but I like the word), Mark is posed in front of an orange oval. This juxtaposition has been a compositional device in Rivera’s work for over a year. In most cases, it works (see panel 1 in Saturday’s strip), because the oval carries across the entire panel, creating a proportionally divided background using a slowly curving line.

But today, we see an oval isolated within a larger panel, unable to reach its sides. Rather than dividing the background, today’s example serves to frame Mark’s figure, like the concentric circles in the opening credits of Warner Brothers cartoons; just not as developed. Was Rivera going after the same aesthetic concept or adapting the device to a different idea? Okay, only art/art history geeks would care one way or another, I suppose. At least I’m not using footnotes.